Having versus Being

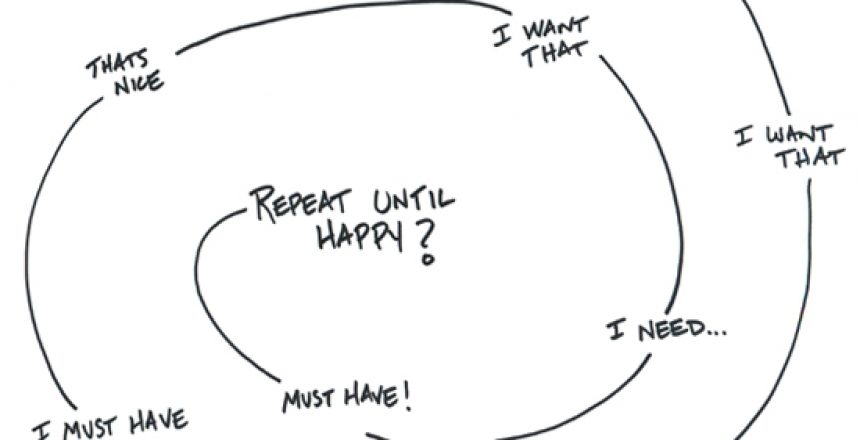

Do you confuse your needs with your wants? Have you caught yourself thinking that you “need a vacation” or “need to try a pumpkin latte”? If yes, your sense of entitlement may be making you lose sight of what you really need versus what you want.

So, where does a sense of entitlement come from? I believe it comes from never having to truly struggle for the basics of life or not appreciating that the basics were provided for you by someone else. If you grew up taking annual family vacations every year, getting brand new clothes for the start of school and enjoying the holidays with tons of new toys, why would you expect anything less as an adult? Now that you’re the grown-up, you have a paycheck and credit cards. You likely take that money and satisfy your sense of entitlement despite the potential long-term costs.

A sense of entitlement can be magnified when you start unconsciously playing “keeping-up-with-the Joneses”. You hear other people talking about their wonderful week in Hawaii or see another mom dressed in a new pair of fall boots, and you feel that you should have those things too. What you don’t realize is that they are staying at a relative’s house and their parents bought the plane tickets, or that they are going into debt for those items. This game can be devastating for your cash flow and set you back years from reaching your most important goals.

So how do you break with a sense of entitlement?

Identify your Needs versus your Wants. Needs are the essentials of life, the basics we cannot live without (basic food and clothing, shelter, health care, childcare and debt payments). Wants are items, activities and services that increase your quality of life. These items can be wasteful if your income is limited and include: eating out, brand name clothes, sports equipment, new cars, music, movies, cable TV, or vacations.

These three simple steps can help you break from a sense of entitlement:

Step 1: Be self-aware. Look at one month of your total spending (all bank accounts and credit cards). Go item by item to see if the spending was a need or want. Mark the Need with an “N” and Want with a “W”. How many “N”s versus “W”’s are there?

Step 2: Create a one month plan for your spending. Make a list of what you need to spend your money on for the next month and your wants. At the end of the month, reconcile your actual spending with this list. How did you do?

Step 3: This one is a real challenge but a great one to try. Pick one day a week that you DO NOT BUY ANYTHING. This means no coffee, no groceries, no nothing. You could modify this and pick one month where you do not buy any wants. Either way, this will likely save you more than you think. On average, families in the Bay Area spend between $7,500-12,000 per month (including mortgage, property tax, insurance and all discretionary spending). That equates to $250-400 per day. If you spent nothing one day each week for a month, that would give you cash savings of $1,000-1,600 per month! If you invested this money for retirement, in 25 years you would have nearly $700,000 (assuming you retire in 25 years and invest at 6%).

Recently I started working with a client that kept a very meticulous budget and separated spending between needs and wants. They had clearly spent time going through the exercise and did not feel ashamed and guilty when showing all the spending on wants. Why? Because they had planned for it pro-actively and only bought what they could afford.

To grow up from a child-like sense of entitlement to a self-sufficient adult takes self-awareness and control. Change can be scary, but as a financial planner, I have seen first-hand how liberating the transition to fiscally responsible adult can be for a person.